China's Evolving Nuclear Command and Control for Launch-on-Warning

A Look at the New C2 Architecture and Doctrine Behind China's Move to "Early Warning Counterstrike."

I recently had the pleasure of joining the Nuclecast podcast (episode out soon) to discuss China’s evolving nuclear C4ISR and the growing impact of AI on its capabilities and doctrine. I want to tackle these topics here now. This post is the first in a series that will explore China’s nuclear C4ISR, beginning with a deep dive into it’s nuclear C2. We will explore the communications and ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) components in subsequent posts.

From Assured Retaliation to Early Warning Counterstrike

For over half a century, China’s nuclear strategy was defined by a doctrine of “assured retaliation.” Underpinned by a public No-First-Use (NFU) pledge, this posture was pragmatic. Facing the vastly larger arsenals of the United States and the Soviet Union, Beijing maintained a small, survivable force designed to absorb a nuclear first strike and then deliver a retaliatory blow sufficient to inflict unacceptable damage. This philosophy shaped a force structure that prioritized concealment and survivability, with warheads kept separate from missiles and a low overall state of alert.

Today, that doctrine is undergoing a major shift. China is moving toward what it calls “early warning counterstrike” (预警反击), a posture known in the West as launch-on-warning (LOW). This is a fundamental change in strategic thinking. Instead of waiting for nuclear detonations on its soil, China is building the capability to launch its own nuclear weapons upon receiving and confirming strategic warning of an incoming attack. The objective is to launch its retaliatory strike before its own arsenal can be destroyed on the ground, thereby ensuring the credibility of its deterrent.

This evolution is driven by Beijing’s fears that advancements in U.S. precision-strike weapons, missile defense systems, and globe-spanning ISR capabilities could neutralize its traditional second-strike capacity. From Beijing’s perspective, this creates intense “use-it-or-lose-it” pressures in a crisis. The ability to launch on warning is seen as a necessary countermove to negate any perceived U.S. advantage in a disarming first strike. While China officially maintains its NFU policy—arguing that a launch triggered by an incoming attack is still technically a “second strike”—this new posture creates ambiguity. A decision to launch, made under immense time pressure based on sensor data, blurs the line between retaliation and preemption and transforms China’s C2 requirements.

The Centralization of Nuclear Command

The pivot to an early warning counterstrike posture would be impossible without the sweeping military reforms initiated in 2015. The reforms reshaped the PLA’s high command, dismantling a ground‑force‑centric structure ill‑suited to modern warfare. One of the most significant changes for nuclear C2 was the elevation of the former Second Artillery Corps into a full, co-equal service branch: the PLA Rocket Force (PLARF; 火箭军). This move gave the PLARF greater bureaucratic clout, a larger budget, and a more direct line to the Central Military Commission (CMC).

At the apex of this new structure is the “CMC Chairman responsibility system” (军委主席负责制). Codified under Xi Jinping, the policy concentrates ultimate military authority—probably including the decision to employ nuclear weapons—in the Chairman’s hands. It ensures the Party, and specifically the Party Chairman, “controls the gun.” In the high-stakes, compressed timeline of a nuclear crisis, there can be no ambiguity or committee-based delay (historically, launch authority required joint approval from the Politburo Standing Committee and the CMC). This personal and centralized control is the linchpin of China’s early warning counterstrike posture.

Hardened Bunkers and the CMC JOCC

Supporting this new doctrine is a massive investment in hardened, survivable C2 infrastructure. For decades, China’s senior leadership has relied on the Western Hills underground command center near Beijing. But recent evidence points to a far more ambitious project: a massive new underground complex west of Beijing, dubbed the “Beijing Military City” by analysts. Satellite imagery shows a sprawling, roughly 1,500‑acre complex that U.S. officials assess to be a national‑level nuclear bunker and wartime command center. With a footprint reportedly ten times the size of the Pentagon, this facility is designed to withstand bunker buster munitions and nuclear strikes, ensuring the continuity of command even in the midst of a nuclear exchange. It’s not clear if the compound will house a separate, dedicated command organ for nuclear C2, as some analysts have speculated, or if the additional infrastructure will support the CMC Joint Operations Command Center’s (军委联指) expanded portfolio over China’s growing nuclear arsenal.

Nonetheless, the new bunker complements the modernized CMC JOCC, the PLA’s supreme, strategic-level operational command body. As the designated Commander-in-Chief of the JOCC, Xi Jinping has been shown in state media overseeing operations from this facility. The existence of these multiple, redundant, and hardened sites ensures that China’s leadership can command its nuclear forces under any circumstances.

While not officially confirmed, it is virtually certain that China has developed a mobile command system analogous to the U.S. “nuclear football.” The concept is well-understood and frequently discussed in Chinese media. Whether it takes the form of a physical briefcase, a specially hardened command vehicle, or a suite of encrypted communication devices, a system likely exists to ensure Xi Jinping is never disconnected from the CMC JOCC and can authorize a strike from any location.

Orders, Authentication, and Control

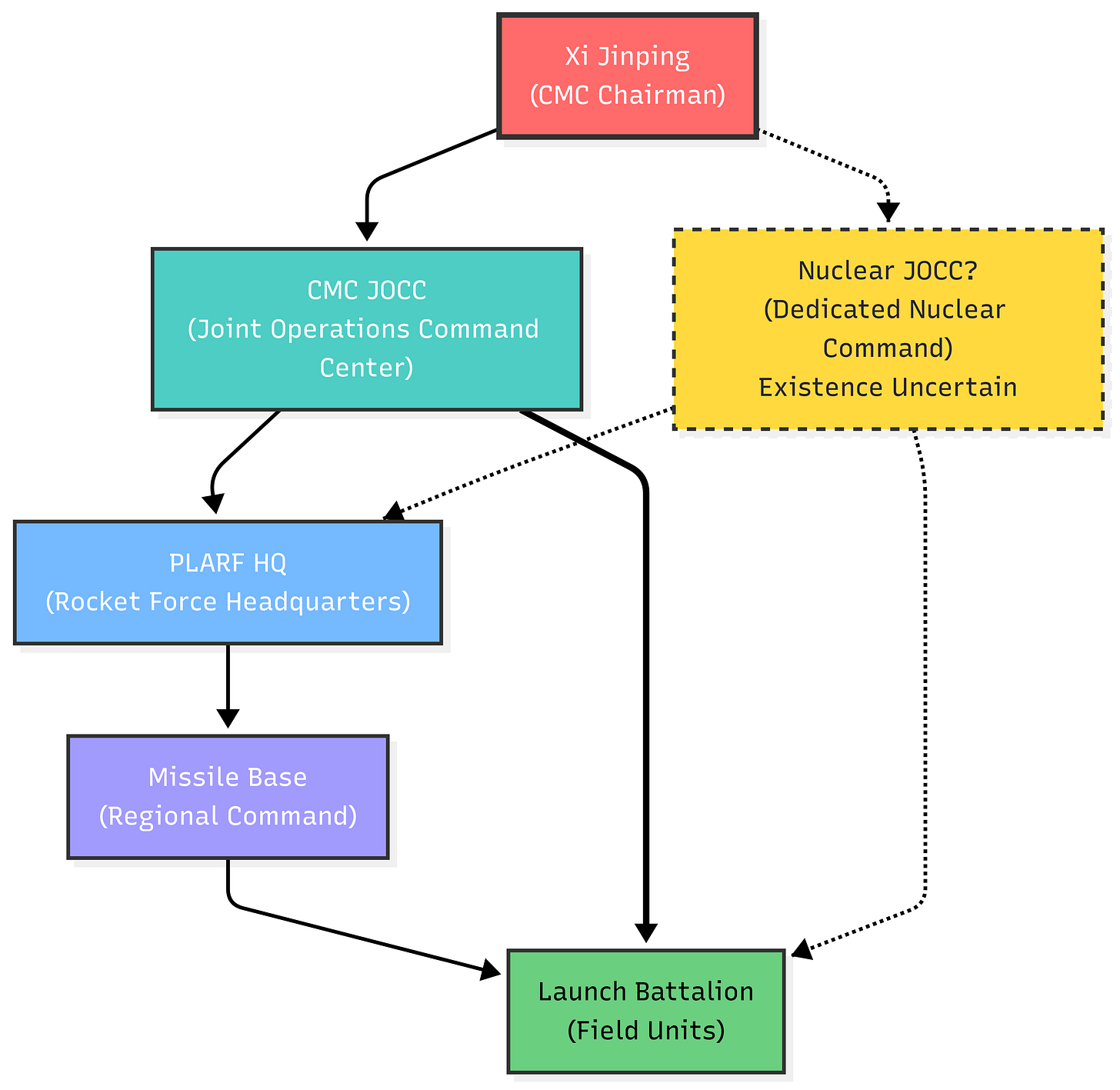

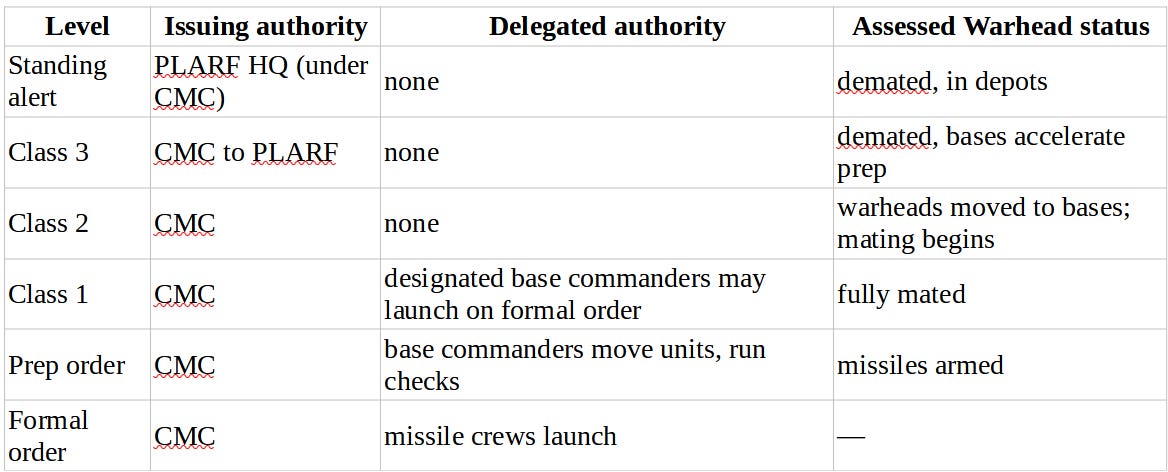

China’s nuclear command system is a four-tier hierarchy designed for strict, top-down control. At the top is the CMC, chaired by Xi, which makes the political decision to launch. The order is then passed to the strategic command level, service-level headquarters (e.g., PLARF HQ), which translates the political directive into a concrete operational order. From there, it goes to the operational unit command level, the various missile bases and brigades, which prepare their forces. Finally, the order reaches the field units—the launch crews who physically execute the command.

An actual nuclear strike order is a highly secure and authenticated directive. Chinese sources reveal it comprises at least three critical documents: the CMC’s order, the PLARF headquarters’ implementation order, and the specific missile launch order. To ensure orders are received even if primary communications are severed, the PLARF maintains “officer liaison teams” that can physically deliver written, top-secret orders to launch brigades. (Most evidence of China’s nuclear doctrine comes from Second Artillery texts; presumably the process is similar for the air and sea leg of China’s emerging nuclear triad.)

This system is built on a careful balance of Negative and Positive Control.

Negative Control, or preventing accidental or unauthorized use, is paramount. It is enforced through the strict, centralized political authority of the Chairman; likely a “two-person rule” at every stage of command transmission, requiring joint authentication between, for example, a base commander and political commissar; and technical safeguards like electronic permissive action links (PALs) on missiles. In peacetime, warheads are also kept demated (separated) from their delivery vehicles, adding a physical barrier to unapproved launch, though this practice would change during a heightened alert.

The DoD 2024 China Military Power Report claims the PLARF maintains “a portion of its units on a heightened state of readiness while leaving the other portion in peacetime status with separated launchers, missiles, and warheads.” There’s debate whether these units on heightened readiness have live warheads mated to missiles, which would be a substantial shift in China’s nuclear posture. Even if warheads are kept demated today, the PLA is likely to deploy at least some units with live warheads in the next few years.

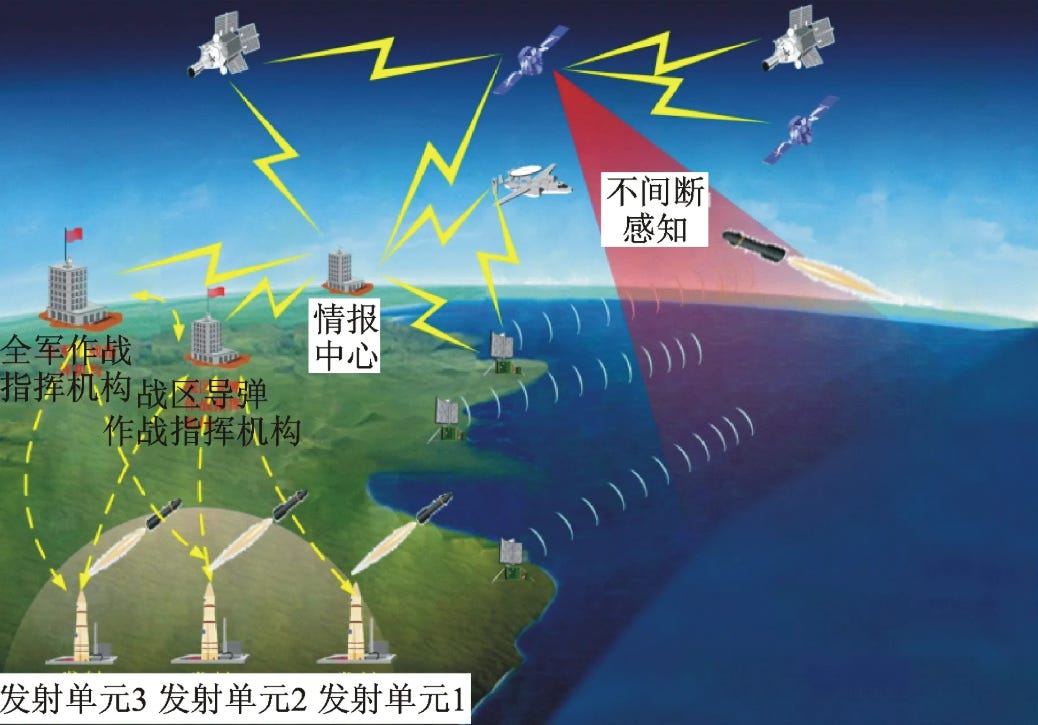

Positive Control, ensuring weapons work when ordered, has been the focus of recent modernization. It is achieved through a multi-layered and redundant communications network of hardened fiber-optic cables, satellite links, and radio systems. The system also features a “skip-echelon” capability, allowing the CMC JOCC to communicate directly with launch crews if intermediate command posts are destroyed. This robust network ensures that an authenticated order can reach its destination even in the chaos of nuclear war.

Integrating AI into Nuclear C2

As China looks to the future, it sees the integration of AI as the key to mastering “intelligentized warfare” (智能化战争). In the nuclear C2 loop, AI is not envisioned as a doomsday machine but as a “smart staff” (智能参谋) to augment human decision-making. The extreme time compression of a LOW posture makes it nearly impossible for human analysts alone to process the vast amounts of sensor data required to make a confident decision.

AI is being applied in several key areas:

Early Warning and Intelligence: AI algorithms can instantly fuse data from satellites, radars, and other sensors to rapidly confirm a missile launch, calculate its trajectory, and assess whether the attack is limited or massive, nuclear or conventional. This provides earlier and more reliable threat assessments.

Decision Support and Planning: In the command center, AI can run thousands of wargaming simulations, generating and evaluating optimal retaliatory strike packages. It can help select targets, deconflict missile flight paths, and predict adversary responses, providing human leadership with a menu of vetted options.

C2 Automation: AI can monitor the health of the C2 network in real-time, automatically rerouting communications around failures or intrusions to enhance resilience.

Despite these ambitions, Beijing has drawn a firm red line: the final decision to launch nuclear weapons will always remain under human control. This principle of “human controls the nukes” (人控核) is a political and ideological imperative. Chinese strategists are acutely aware of the risks of AI, from algorithmic bias and false alarms to cyber vulnerabilities. In 2024, the U.S. and China found rare common ground in agreeing on the need to maintain human control over nuclear weapons. For a decision of such gravity, the CCP leadership will not delegate its authority to a machine.

Conclusion

China is on a clear and irreversible trajectory toward fielding a robust early warning counterstrike capability by the end of the decade. This transformation has profound implications for the United States and strategic stability.

On one hand, China’s more survivable and responsive nuclear force strengthens deterrence by denial. It complicates any adversary’s calculus for a successful first strike, arguably contributing to stability by making nuclear war less thinkable. On the other hand, a launch-on-warning posture is inherently fraught with risk. It creates a hair-trigger dynamic where monumental decisions must be made in minutes based on potentially incomplete or ambiguous information. The entanglement of nuclear and conventional C2 infrastructure, combined with the deployment of dual-capable missiles, creates dangerous pathways for miscalculation and inadvertent escalation.

This new reality presents a formidable challenge. It fuels a classic security dilemma, potentially accelerating a tripolar arms race between the U.S., Russia, and China in the absence of Cold War-era treaties. For the United States, effectively navigating this new, more complex nuclear landscape will require a deep and nuanced understanding of China’s capabilities and intentions, a renewed focus on crisis management and communication channels, and a sober reassessment of the requirements for a stable deterrent in the 21st century.

Thanks for reading! I hope you found this useful. The next installment will examine China’s nuclear ISR and early-warning enterprise. Please subscribe to Orders and Observations, share the newsletter, and follow me on X/Twitter and LinkedIn if you’d like to connect or collaborate.

Excellent and eye opening information.I suggest author to do detailed comparative analysis of nuclear doctrines and C4I procedures of different countries with pros and cons of adopting AI for these systems .

Exceptional. AI part is most innovative and interesting. An important take away is, despite AI and other technologies, primacy of “Human Control”. The concept of LOW while theoretically possible has the potential of inadvertently starting nuclear conflict.