China's Military Satellite Communications

PLA SATCOM Infrastructure, C2, and Operational Employment

In my last two posts, I covered the evolving C4ISR architecture and operational concepts behind the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) autonomous airpower. A key theme that emerged from that analysis was its growing dependency on resilient, long‑haul communications to make these systems work, particularly as Beijing seeks to project power far beyond its shores. I want to expand on that point now and explore a foundational pillar of the PLA’s global ambitions: its rapidly evolving military satellite communications (SATCOM) architecture.

For decades, the PLA was an earth‑bound force, tethered to terrestrial fiber‑optic cables and line‑of‑sight radios. Its ability to command forces over the horizon was limited and relied heavily on leased capacity from foreign and domestic commercial satellites (a critical vulnerability for any aspiring great power). After watching U.S. operations in the 1990s and early 2000s, Chinese strategists recognized this gap and began a long‑term, state‑directed effort to build an indigenous military SATCOM network.

That effort is now paying dividends. As of last year, DOD assessed that China “owns and operates more than 60 communications satellites, with at least four dedicated to military use.” In other words, in less than twenty years China has moved from a modest regional capability to a multi‑layered global infrastructure that enables the PLA’s modern war‑fighting concepts. Without it, Beijing’s talk of “informatization” (信息化) and “intelligentization” (智能化) would ring hollow. Let’s unpack that architecture, examine the organizations that manage it, and consider the vulnerabilities this new dependency creates.

The Pillars of the Network

China fields several dedicated constellations, many of which launch under the Zhongxing (中星, “ChinaSat”) label—a dual‑use brand that blurs civilian and military roles. This architecture is a layered system‑of‑systems, with each constellation designed to fulfill a specific requirement, from strategic command to tactical data links.

The strategic backbone is the Shentong (神通, “Divine Connectivity”) series of satellites. These large platforms, built on the modern DFH-4 and DFH-4E satellite buses, reside in geostationary orbit (GEO) and function as the PLA’s private broadband network. Analogous to the U.S. Wideband Global SATCOM (WGS) system, Shentong provides high-data-rate, secure links using Ku‑ and Ka‑band frequencies. These are the pipes that connect national leadership in Beijing to Theater Commands and deployed far‑seas task groups, ensuring the PLA’s highest echelons can communicate reliably.

Complementing this is the Fenghuo (烽火, “Beacon Fire”) series, the PLA’s workhorse for tactical forces. Also in GEO, these satellites are more akin to the U.S. Mobile User Objective System (MUOS). They carry UHF and C‑band payloads, frequencies better suited for penetrating foliage and less susceptible to rain fade, making them ideal for mobile users (e.g., ships, aircraft, and maneuver brigades) with small, disadvantaged terminals. Later Fenghuo-2 models have added Ka‑band channels and feature large, 4.2-meter deployable UHF antennas to improve links with even the smallest ground terminals.

Recognizing the need for individual connectivity, China developed the Tiantong‑1 (天通一号, “Heavenly Link‑1”) system to supply handheld satellite telephony. Born from the lessons of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, which severed terrestrial communications, Tiantong-1 is China’s indigenous version of Iridium or Inmarsat. In a clear example of military-civil fusion (军民融合), the service is operated commercially by China Telecom but grants the PLA priority access and uses hardware‑level encryption when required. The integration of Tiantong service directly into Huawei consumer smartphones has made a secure, beyond-line-of-sight communication channel ubiquitously available across the force and government. (While primarily a GPS analogue, I’ll also note Beidou’s burst SMS capability provides a austere backup for position reports, emergency tasking, and network timing when regular SATCOM is jammed or unavailable.)

Perhaps most critical for enabling the PLA’s long-range kill chains is the Tianlian (天链, “Sky Link”) series. These are China’s data‑relay satellites, analogous to the U.S. Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS). They act as “satellites for satellites,” using S-band and Ka-band links to grab data from low‑earth‑orbit sensors, such as Yaogan ISR satellites, and relay it straight back to China. This capability is a profound force multiplier, as it closes the “blind time” that once forced a spy satellite to wait until it was over a friendly ground station to downlink its imagery.

Command and Control

Managing this complex celestial infrastructure requires an equally sophisticated command-and-control (C2) apparatus. The April 2024 reform that dissolved the Strategic Support Force (SSF) clarified these lines of authority, creating two new arms with distinct responsibilities for space operations.

The Aerospace Force (军事航天部队) is the new “asset provider.” It owns the satellites, launch vehicles, and the vast majority of telemetry‑tracking‑and‑control (TT&C) assets. Its mandate covers the entire lifecycle of a space system, from development and launch to on-orbit operations and eventual decommissioning. Alongside it, the Information Support Force (信息支援部队) serves as the dedicated “network integrator.” The ISF’s core mission is to stitch together the PLA’s disparate networks—space, terrestrial, and cyber links—into a unified information grid. This includes the complex task of allocating bandwidth and deconflicting spectrum, likely in close coordination with the State Radio Regulation Bureau under the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology.

Daily spacecraft operations center on the Xi’an Satellite Control Center (XSCC), the nerve center of China’s space network. From this hardened facility, PLA engineers monitor the health and status of hundreds of satellites, execute precise orbital maneuvers to reposition them or avoid debris, and task their onboard payloads. While the Beijing Aerospace Flight Control Center still directs high-profile crewed and deep‑space missions, it is Xi’an that handles the day-to-day work of managing the SATCOM constellations.

Xi’an now presides over a greatly expanded domestic TT&C network designed for redundancy and comprehensive coverage. Ground stations in Weinan, Kashgar, Sanya, Changchun, Jiamusi, and Qingdao, among others, form a robust national web for commanding satellites as they pass over the mainland.

A Global Web of Ground Stations

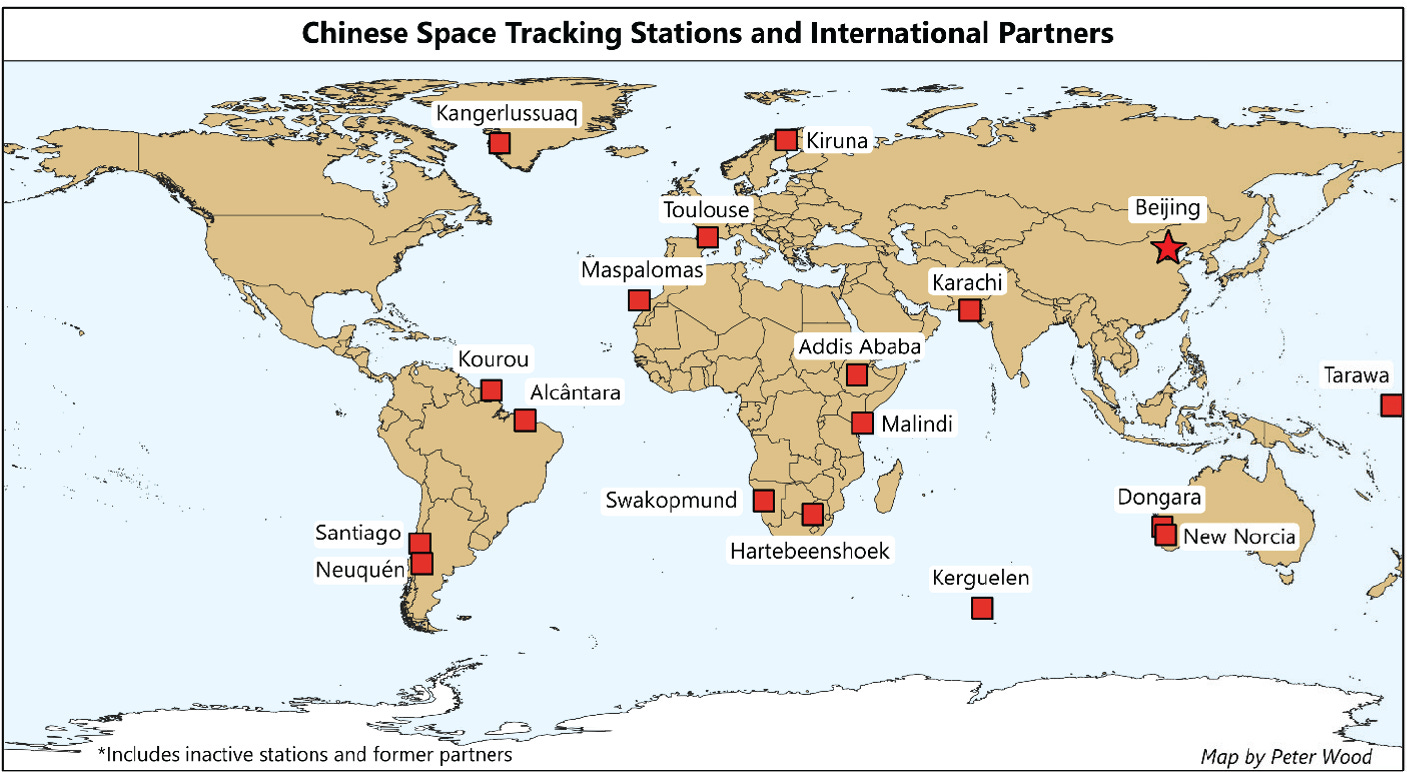

A domestic network is insufficient for controlling a global satellite fleet. To solve this, China complements its home‑territory network with a growing string of overseas sites that provide persistent coverage across all longitudes. In addition to the well-known deep-space station in Neuquén, Argentina, the PLA uses ground stations in Karachi, Pakistan, and Swakopmund, Namibia. Beijing also operates a down‑range antenna complex in Malindi, Kenya, which provides crucial coverage over the Indian Ocean and Africa.

Often established under the guise of “scientific” or “civil” projects within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative, these facilities provide the PLA with pre‑emptive access to command its satellites and downlink data from anywhere in the world. This global infrastructure is backstopped by the Yuanwang (远望) tracking‑ship fleet and new Liaowang-1 (瞭望1号, Observer-1) space support ships, which can deploy to any ocean to plug coverage gaps during critical launch and early‑orbit phases, ensuring China never loses touch with its valuable space assets.

The Network in Action

This architecture of satellites and ground stations enables the PLA’s modern warfighting concepts. Consider the kill chain for an anti‑ship ballistic‑missile strike on a moving aircraft carrier. A Yaogan satellite detects the carrier group, but it is over the Pacific and out of sight of a Chinese ground station. It uploads the track data via Ka-band to a Tianlian relay satellite in GEO. Tianlian immediately downlinks the data to a ground station which pipes it to an analysis center. There, analysts correlate the space-based intelligence with other sources, like over-the-horizon radar returns, and transmit a refined firing solution through a secure Shentong satellite link to a DF‑26 brigade. After launch, the missile receives in-flight updates on the carrier’s new position, relayed through a Fenghuo satellite, allowing it to adjust course and home on a target hundreds of miles away. This entire sequence, which unfolds in minutes, would be physically impossible without a sovereign, multi-layered SATCOM architecture.

The same network underwrites the PLA Navy’s transformation into a blue-water force. A PLAN destroyer on anti-piracy patrol in the Gulf of Aden no longer relies on finicky, low-bandwidth HF radio. It now uses Shentong for high-speed command communications, beams reconnaissance imagery from its helicopters back to the mainland via Fenghuo, and uses the Tiantong service for logistical support and crew morale calls. It operates as a fully networked node within a global C4ISR grid, a capability that is the very definition of a modern, great-power military.

The LEO Ambition

Beijing’s next move is into low-earth orbit. Its Guowang (国网, “National Network”) is a planned constellation of roughly 13,000 satellites managed by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC). This effort is a direct response to the demonstrated military utility of SpaceX Starlink. Guowang promises to provide a dense, resilient, low-latency network that is far more difficult to degrade than the handful of large, exquisite satellites in GEO. To support this massive undertaking, China is building a new industrial base, including satellite “super-factories” capable of mass production.

Yet, this ambition highlights the central paradox of the PLA’s modernization. By building this new infrastructure, the PLA is creating a new center of gravity. The ground segment, with its fixed and easily located antennas in places like Argentina and Namibia, presents a set of high-value targets. The satellite uplinks and downlinks are inherently vulnerable to sophisticated electronic warfare, including jamming and cyber intrusion. The GEO satellites themselves, each representing a massive investment and a critical capability, are lucrative marks for anti‑satellite weapons. China’s own 2007 anti-satellite test revealed both the feasibility and the immense collateral risk of such strikes, creating a tense deterrent posture in the space domain.

Closing Thoughts

By building a sovereign SATCOM architecture, the PLA has given itself the connective tissue it once lacked, enabling it to command forces, share intelligence, and project power on a global scale. This same network, however, now forms a new and potentially fragile dependency. In any future conflict, the contest to protect or to sever these links in space will be as decisive as the struggle for control of the air or the sea. Tracking China’s growing TT&C and ground station infrastructure will be critical for identifying PLA overseas presence and potential vulnerabilities. More work also needs to be done parsing the division of responsibilities between the ASF and ISF for operation of SATCOM infrastructure, as well as analyzing how these organizations intend to defend PLA C3 capabilities in a high-end conflict.

We’ll tackle these and other topics and future posts. Stay tuned! And as always, please subscribe to Orders and Observations and share my newsletter if you enjoyed this post, and follow me on X/Twitter and LinkedIn if you’d like to connect or collaborate.

Thanks for another interesting and informative article.